The following is a guest contribution from Heather Brittany (@HeatherBrit). Heather is currently a law student at Loyola Law School, Los Angeles and Sports Chair of its Entertainment & Sports Law Society.

The pay-for-play argument has long surrounded the world of college athletics. It is no secret that athletic programs (specifically football and basketball teams) bring universities millions, even billions of dollars. Although, even that notion may be somewhat misguided as many argue that the majority of universities are actually running their athletic programs (as a whole) in the red. However, that analysis is for an economist. Therefore, for the sake of argument, let’s stick with the common perception that these programs are generating huge amounts of income for universities and the NCAA.

The main point of contention surrounds the notion of scholarships as “payment.” The NCAA and universities state that by providing athletes with a free education they are promoting amateurism and the student-athlete. In the October issue of the Atlantic, there is an article, written by Taylor Branch, The Shame of College Sports, which attempts to dissect (and destroy) the glamorized image of the “student-athlete.” Branch writes,

“For all the outrage, the real scandal is not that students are getting illegally paid or recruited, it’s that two of the noble principles on which the NCAA justifies its existence—“amateurism” and the “student-athlete”—are cynical hoaxes, legalistic confections propagated by the universities so they can exploit the skills and fame of young athletes.”

I share Branch’s sentiments that the theory of amateurism is a hoax, or at least, not a compelling justification. However, the idea that the existence of the “student-athlete” is nothing more then a legal confection is a far cry from reality.

Advocates for the players discredit the value of a scholarship with arguments that the players do not care about their education. They state that a scholarship for a NFL-hopeful is meaningless and that the only reason players attend college is because they have to, if they have any hopes of making it to the pro’s. These commentators are likely correct. However, they either have a disillusioned view of why most students are at universities, or they are simply forgetting that anyone outside of the student-athlete attends school.

I would argue, that the majority of college students are there not because they are so enthralled in the mysteries of an education, but rather because they have some higher goal, which requires a degree. Do these people honestly think that students would take out over a hundred thousand dollars in loans, spend 16 hours a day in the library or class, and completely kiss their social life goodbye if they didn’t have to? Hell no. They are doing it because they have dreams of one day becoming an attorney, a professor, a doctor, etc. and unfortunately, one of the ways to get there is to pay a university.

Technically, one does not need a degree to pursue his corporate dreams; similarly, athletes do not have to attend college to become professional athletes. However, it is well known that the surest and safest means of reaching these goals is by attending school. Therefore, many people go to get their degree, not because they want to, but because they have to for the next step. For athletes, many are able to do this with little to no financial risk of their own.

Like it or not, the NCAA is the governing body of most college athletics. Branch writes, “The NCAA, in its zealous defense of bogus principles, sometimes destroys the dreams of innocent young athletes.” There is no debate that the NCAA deals erroneous and questionable rulings when investigating infractions. However, the NCAA does not destroy a player’s dreams just for shits and giggles. If I choose to cheat on an exam, and this is proven, my school would have every right to not only fail me out of that class, but to kick me out of school. Would I have the defense that the school destroyed my dreams? No. This attempt to skirt accountability for one’s actions is fatally flawed.

Next, is the argument surrounding universities’ large endorsement deals.

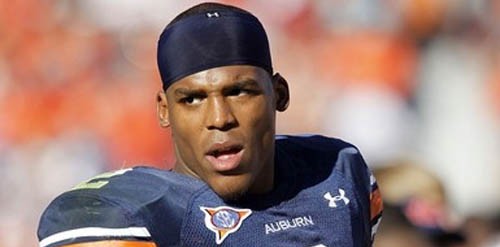

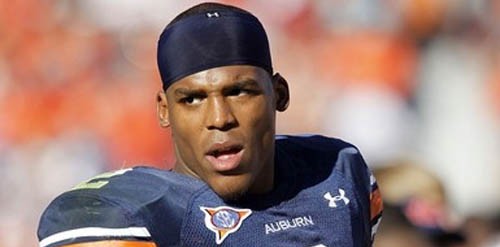

“Last season, while the NCAA investigated him and his father for the recruiting fees they’d allegedly sought, Cam Newton compliantly wore at least 15 corporate logos—one on his jersey, four on his helmet visor, one on each wristband, one on his pants, six on his shoes, and one on the headband he wears under his helmet—as part of Auburn’s $10.6 million deal with Under Armour.”

Interestingly enough, Branch omits the fact that Cam Newton, after only playing for Auburn for one season, signed a record-breaking (over $1 million dollars a year) shoe and apparel deal with Under Armour. However, Branch, quoting retired LSU basketball coach Dale Brown, writes “Look at the money we make off predominantly poor black kids… we’re the whoremasters.” I am hard-stretched to believe that Under Armour would have offered Newton that deal if it were not for the exposure he received from Auburn. Furthermore, was it not Auburn who gave Newton that second (or third) chance?

Another point of contention is the theory of eligibility. Branch sites the story of James Paxton to illustrate this NCAA rule. Paxton decided, after his “attorney” negotiated with the Toronto Blue Jays, that he would stay in college. Unfortunately, NCAA rules do not allow a collegiate athlete to negotiate terms with professional teams. Therefore, after deciding that he wanted to stay in college, the NCAA forced Kentucky to not allow him to play. Is this the right rule? Maybe not. (A player should have some rights in testing the waters to see what his stock is. However, allowing him to fully go through the draft and then opt to return to college would be detrimental to all professional teams who systematically and carefully rely on their draft choices). But, is it THE rule? The answer is yes. Therefore, Paxton was called to abide by it, just as the millions of other student-athletes are. If you don’t like it, go change it.

Additionally frustrating is the NCAA’s rule of only allowing schools to issue one-year scholarships. Joseph Agnew, “a student at Rice University in Houston, had been cut from the football team and had his scholarship revoked by Rice before his senior year, meaning that he faced at least $35,000 in tuition and other bills if he wanted to complete his degree in sociology. Bereft of his scholarship, he was flailing about for help,” writes Branch. Agnew brought suit against the NCAA asking the federal court to strike down the NCAA rule that prohibits colleges from offering any athletic scholarship longer than a one-year commitment. “The one-year rule effectively allows colleges to cut underperforming ‘student-athletes,’ just as pro sports teams cut their players. ‘Plenty of them don’t stay in school,’ said one of Agnew’s lawyers, Stuart Paynter. ‘They’re just gone. You might as well shoot them in the head.’”

Quite frankly, losing your scholarship sucks. However, I wouldn’t equate it to being shot in the head. If you get cut from the team, it means you were not performing at the level that was expected you, or simply, someone else beat you out. Guess what? This happens all of the time for students who are admitted to a school with academic scholarships. Many of those students will work for endless hours, exuberating more effort and dedication then they ever have before. Unfortunately, many of them will fall short. Subsequently, they will lose their scholarships and will be faced to pay for their remaining years’ tuitions if they want to complete their degree. Guess what they do? Student loans (dun duuuuuun).

Although Agnew’s case was recently dismissed, the idea of abandoning the one-year scholarship limitation should not be. The NCAA regulates the maximum number of athletic scholarships a university can distribute per team and also mandates that they can only give one scholarship at a time. The first part of this rule makes sense. If schools were allowed to distribute as many scholarships as they wanted, private universities would completely control the world of collegiate athletics. Because of the clout, recognition and excitement that a good football program can bring to a school, it is important to create, somewhat, of a level playing field.

On the other hand, the one-year length restriction does not have any logical rationale. For example, if a university recruits a player who stays for all four years, that scholarship counts once for each year that he is there. If the university decided it really wanted a player and gave him a guaranteed four-year scholarship, the scholarship would still only count once for each year that he is there. Granted, it is a huge risk and most universities would only offer a very limited amount of said scholarships. However, the big name schools as well as the smaller schools would both be losing the same amount of scholarships, one scholarship for each year that he stays.

This would allow players to engage in more of a free-market as they decide where to begin their collegiate career. For example, a player may be offered a 1-year (unilaterally renewable) scholarship at Alabama and may be offered a 4-year guaranteed scholarship from Rice University. He would then have to weigh the benefits and risks of each school and decide which school he wanted to go to – the one with the bigger name, or the one where he was guaranteed a fully compensated degree. This allows for both the universities and the players to engage in a risk-reward analysis (this is currently regular practice for academic scholarships, schools offer some students full scholarships and others are grade contingent – the student has to choose, guaranteed money or the more competitive school).

Last, is the issue of grades. Statements that student-athletes have a propensity to cheat, and that professors are pressured into padding their grades, are nothing new. This does not mean that the value of an education is nonexistent. It does, however, present another problem that must be handled at the university level. It is true that some schools have more rigorous academic standards then other schools do and therefore it is harder for athletes at those schools to both excel on and off the field. In that case, the university must be prepared with all the academic support that their players may need. Universities know an athlete’s high school GPA before they give him a scholarship; therefore, they must be prepared for any additional academic hurdles.

Branch writes, “Nothing in the typical college curriculum teaches a sweat-stained guard at Clemson or Purdue what his monetary value to the university is. Nothing prods students to think independently about amateurism—because the universities themselves have too much invested in its preservation. Stifling thought, the universities, in league with the NCAA, have failed their own primary mission by providing an empty, cynical education on college sports.”

Although Branch is overly cynical about the goals and attempts of universities, he alludes to a valid point. There absolutely is a need for universities to properly educate their athletes. As I have previously written, universities must implement specific programs to provide tailored educational opportunities to student-athletes. Some universities do have a “Professional Sport Counseling Panel,” however no university, to my knowledge, has a fully developed program aimed specifically at the unique scenarios a student-athlete faces.

There is also the argument that a player should have a right to his likeness. This is currently being contested in a class-action suit against the NCAA and EA Sports. While only time will tell what the courts decide, I do believe that universities should not reap the full benefit of a player’s likeness – after he graduates. Once he graduates, he should be able to collect a substantial percentage for the continued use of his likeness. Not in back pay, or in likeness previously used, but if the NCAA, EA Sports, universities, or whomever, decide to continue using his persona, he should have a right to be paid for his likeness. If the athlete decides to go pro before completing his degree, then he should not receive royalties for his likeness. That is, until he completes his degree.

Although the monetary benefits to a university outweigh that to which a student receives while attending the school, by no stretch of the imagination does “It echo… masters who once claimed that heavenly salvation would outweigh earthly injustice to slaves.” The value of a degree is undeniable and the opportunities created by attending a university are limitless. Sure, the university makes a lot of money off of its students; however, this is true whether the student is the starting quarterback of the school’s football team or pursuing a medical degree. Hopefully, the student utilizes all that the university offers to fully enrich, build, and prepare himself, and his career, for the future. If he does, he is likely to see monetary and personal benefits beyond what his university received on his behalf.