According to Statista, the revenue of the North American sports sponsorship market was estimated at approximately 17.17 billion U.S. dollars in 2018 and is expected to grow to over 20 billion U.S. dollars by 2022. One may be rightfully skeptical of that anticipated increase amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Without triggering PTSD, let’s rewind to March 11, 2020. On the heels of a positive test of a Utah Jazz player, the NBA swiftly postponed the infamous, Wednesday night Jazz-Thunder game. Soon after, Adam Silver and co. postponed the 2020 NBA season, a significant move that others would later follow, both in and out of the industry. That same Jazz player may or may not have rubbed his hands all over press microphones in jest that same day, but that’s neither here nor there. The focus of this article is the impact that postponed games and empty stadiums have had on sponsorship agreements between leagues and brands.

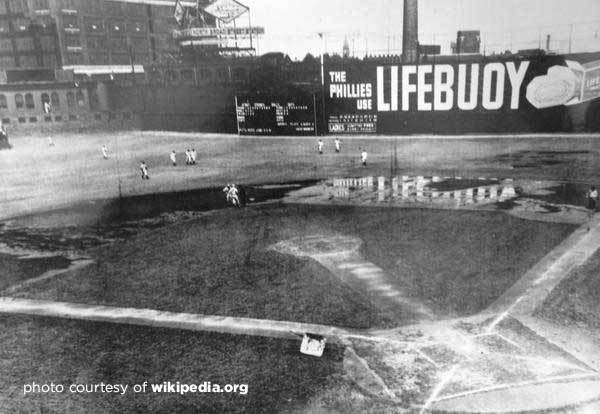

Sports leagues and teams have long recognized, and taken advantage of, the monetary potential of advertising with brands. Did Cracker Jack pay for its shoutout in the iconic, 1908 “Take Me Out to the Ballgame?” Let’s assume an innocence from capitalism to preserve the purity of the jingle. The most classic sponsorship agreement in sports typically features physical advertisements displayed at live sporting events. One of the earliest examples comes from a soap company, Lifebuoy Soap. The company logo was displayed on outfield billboards during MLB games in the 1920s and ‘30s.

Now, we see outfield walls and scoreboards littered with advertisements. It serves as a minor eyesore to fans and a major revenue source for MLB.

Baseball is not alone in this practice. The PGA Tour has over 40 official marketing partners. Included in those sponsorship agreements are the “Official Tire of the PGA Tour” and the “Official Meat Snack of the PGA Tour.” The contractual agreements allow for various methods of getting brand names to consumers, both physically and digitally. A single Tweet can be worth millions of dollars, camera angles intentionally capture brand names, and companies run up the bidding on naming rights and commercial airtime. However, as previously mentioned, the most classic form of advertising is the physical display at a live sporting event. Competing with this notion is the fact that the past 12 months have allowed for little to no fans at sporting events to actually see these displays.

By just April of 2020, sport shutdowns had disrupted an estimated 120,000 sponsorship agreements with over 5,000 brands. Companies and sports teams negotiate sponsorship agreements based on a projection of value for both sides. What happens when that original projection is rendered impossible, through the fault of neither of the parties? In the words of Andrew Brandt, “there will be lawyers.”

Sponsors rightfully want to rework contracts with teams and leagues; “we pay to advertise at your events and now no one is there.” On the other side, leagues are suffering across the board in their own right and can’t afford to lose the sponsorship money they fairly contracted for. The biggest driver for revenue at most PGA Tour events is the corporate hospitality tents. That money is largely off the table without fans. With that, venue owners are working to mitigate their financial exposure to sponsors, and sponsors are working to ensure that they receive the commercial spotlight and value they pay for.

These competing interests have led to discussions around contract provisions and carve-outs that are typically only discussed in law schools. One such provision is the “make-good” obligation or requirement. This provision covers situations where a venue is unable to provide a sponsor with the value they reasonably excepted under the terms of the contract. Once triggered, the venue will work to provide the sponsor with a value comparable to or greater than the original expected value. This often ends in disagreement and resulting arbitration.

Regardless, leagues will have to address these obligations by either diluting the existing sponsorship channel’s value or by finding new sponsorship opportunities. Many contracts outline, in great detail, what constitutes a breach of performance with accompanying liquidated damages. However, it’s highly unlikely that a sports league or team would be held in breach when they were forced to vacate their venue due to government-mandated public gathering limits.

This sentiment has led some teams and leagues to claim force majeure (French for “superior force”). Under force majeure, neither party will be liable for failure to comply with any of the terms of their contract when such failure to comply has been caused by fire, war, insurrection, labor disturbances, work stoppages, terrorism, government restrictions, natural disasters, weather, or acts of God beyond the reasonable control of the parties. Those are just boilerplate examples of force majeure “events,” individual contracts may read differently. Questions have followed over specific event language and become the subject of litigation across the country. Is a pandemic an act of God? Can the spread of virus, likely stemming from human or animal activity, be considered an act of God? The agnostic quickly rejects both theories but sports leagues vehemently contend that God has acted.

The second force majeure possibility lies in the term, “government restrictions.” This leads to a chicken and egg debate where the parties argue over what is the “real” superseding event. Leagues and teams contend that government-mandated limits on public gatherings have rendered performance of sponsorship agreements impossible, therefore triggering force majeure. Sponsors will argue, in response, that it is the COVID-19 pandemic that led to the venue’s inability to perform. The “government restrictions” are only a by-product of a larger event that has preceded failed performance. And by the way (they argue), force majeure does not cover global pandemics. This leads to complex litigation where both sides have legitimate positions.

No matter the outcome of contractual negotiation or litigation, sports leagues need to roll up their sleeves and get creative as fans slowly return. Brian Oliver, the PGA Tour’s Executive Vice President for Corporate Partnerships, says experiences offered to sponsors in the current environment are simply different from those pre-pandemic. “We have adjusted to the reality we are in.” Tickets were not made available to the general public for the Cologuard Classic at Omni Tucson National Resort. Phil Mickelson and Jim Furyk headlined a stacked field for the PGA Tour Champions tournament in Tucson. Yet, tournament spectators were limited to 200 or less, an uninspiring number for sponsors.

The PGA Tour announced that Workday, Inc., depicted on Mickelson’s shirt above, and a leader in enterprise cloud applications for finance and human resources, became the title sponsor for the newly-named Workday Championship at The Concession, held in Bradenton, Florida. Due to logistical challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, the 2021 event was moved from Mexico City to The Concession Golf Club in January. “With the challenges we’ve faced with the pandemic in the last 12 months, Workday has been the epitome of a true partner and this announcement of their support of our relocated World Golf Championships event in Florida is further evidence of their commitment to golf and the PGA Tour,” said PGA Tour Commissioner Jay Monahan. “Our sincere thanks to Workday for their support of what we anticipate will be a world-class event at The Concession Golf Club.”

Another league that has impressed with creative solutions is the NHL. To offset sponsorship losses from the absence of fans, the NHL has flirted with unique ways to promote brands. In their newly realigned divisions: East, West, North, and Central; each features a sponsor as the official division name. For the first time in league history, the NHL has allowed teams to make their own deals to display advertiser’s logos on players’ helmets (some more fitting than others, see below). Finally, some teams have toyed with television camera angles, in an effort to capture more advertisements in a shot by zooming out.

A member of a leading hockey agency told Sports Agent Blog that he thinks the NHL “has done a good job of finding new streams of revenue during these unprecedented times.” “Nothing can replace the lost revenue these last two seasons from ticket sales, gate revenue, etc., but the League has shown their desire to get innovative here.” “From the helmet logos and division sponsors to the games in Lake Tahoe, they have done a nice job.”

He provided a lens to the players’ perspective: “the guys really just wanted to get back on the ice as safely as possible and get as much of their paycheck as possible.” “Hopefully, these ideas can continue into future seasons and produce other creative revenue-generating ideas.”

The New York Rangers went 326 days without fans in the world’s most famous arena but welcomed them back with open arms Friday night. Upon submission of a negative COVID-19 test, 2,000 fans were allowed to enter the Garden, where they witnessed a blueshirt upset over the Boston Bruins. The return of fans is the most direct way to curb sponsorship losses; however, governments care more about citizen safety than private contracts.

Fortunately, many sports sponsorships are sheltered from short-term disruptions because agreements typically span more than one year, said Sean Barror, managing director of Allied Sports, a unit of AALP Inc., which does business as the marketing firm Allied Global Marketing. For example, a six-month disruption is less hard on a company that has a 10-year stadium naming rights deal. That is not the case for the vast majority, however, and sports leagues will continue to do what they can to stop the bleeding in lost sponsorship revenue.